Posted: Sep 16, 2013 9:23 pm

Quaker wrote:Thank you Cali

But you do still seem to be begging the question. Why is social concern for others 'good' when other forms of evolved behaviour that involve physical violence between the members of the species (often males competing for mating rights) 'bad'?

Er, I'm not begging the question, I answered it. For a social species, maximising harmonious interaction between members of a group thereof confers manifest benefits, in the form of energy no longer being wasted in conflict (a principle I'm sure that any Quaker would agree with), said energy therefore being made available for other productive tasks. In order to achieve this, members of that social species need to develop at least some basic cognitive machinery aimed at facilitating this, and one elegant way of doing so is to bestow upon said individuals the means to picture themselves in the position of others. Once empathy and selection for reciprocity is in place, the rest follows naturally. Namely, that members of a social species define 'good' as that which results in maximum benefit and harmony, and minimum conflict. As can be seen in those primates observed by Frans de Waal. Even if they don't understand that they're doing this on the level of abstract reasoning, that is what they are doing. Indeed, in my previous post, I explicitly stated that the New Testament recast this process as an ethical axiom. You might wonder why this was so, given that the part about "do unto others" is directly at variance with the Old Testament "eye for an eye" axiom.

Quaker wrote:What is the empirical evidence to say one is ethically superior to the other?

One produces far fewer corpses and maimed individuals. Next?

On a less facetious note, we have abundant evidence that life is better for us all if actions consonant with the rule of reciprocity are encouraged, than in the converse caee. Which is almost certainly why the NT converted it into an axiom.

Moving on ...

Quaker wrote:MacIver wrote:That's an excellent question.

As a atheist-agnostic and (I guess) a moral relativist I don't think there's an easy answer to that question. But I will say that "good" behavior is "good" because I deem it to be so - no more and no less. This is related to my belief that acting good for the sake of it is more worthy than acting good because of the carrot and stick of existential reward or punishment. You can debate until the cows come home whether altruism really exists. But if it does I hold that nontheists are closer to it than theists.

I'm not a moral relativist, but I don't think there are any easy answers to always being sure what is 'good' and what is 'bad'.

And this brings me to another of the themes you'll find in past posts of mine, namely, that one is far more likely to obtain reliable results in this vein, by actually thinking about the issues, than by simply assuming mythology magically contains all the answers. Especially when demonstrating that mythology doesn't have all the answers is an elementary exercise.

Quaker wrote:Unlike Cali, I do not see clear answers in science or empiricism.

Oh, you don't think hard eperimental evidence supporting a given postulate provides clear answers? What was that about "embracing science" you said earlier?

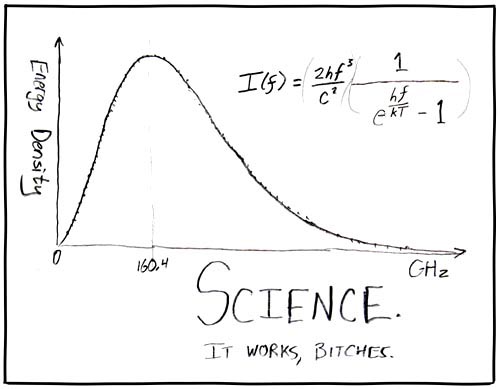

I'm reminded at this juncture of this cartoon from XKCD:

On the other hand, mythology frequently doesn't work. See my numerous past expositions on 1348 and the Black Death.

Quaker wrote:I see more pragmatic use in dialog, 'contemplation', and story telling.

Unfortunately, these have been used by propagandists for doctrine to spread bad ideas. That's the beauty of the scientific approach. It has a habit of weeding out bad ideas before they become pernicious, usually by demonstrating that observational reality disagrees with said bad ideas[ b]strongly[/b].

Quaker wrote:I would say, along with the Pope it seems, that we do have the ability to discern good and bad in our conscience (though I find many grey areas myself)

Er, what was that I posted previously? Oh, that's right, close on a dozen scientific papers demonstrating that the "conscience" is not only a product of our biology, but associated with a specific brain region. Did you read any of that material?

Quaker wrote:and sometimes a collective conscience may be of benefit.

Once again, do tell us all how mere assertions are purportedly "superior" to evidence with respect to this. I'm still waiting.

Quaker wrote:But all of this presupposes that good and bad do exist

No it doesn't. Not in the light of the knowledge that 'good' and 'bad' are terms we define as a result of applying reciprocity. Unfortunately, some have a habit of defining 'good' and 'bad' in terms of doctrinal assertions instead, and that's usually when the body county starts growing.

Quaker wrote:and I find it hard to see how those terms can be grounded soley in materialism or a study of developmental biology.

Read those papers and learn how.

Quaker wrote:The problem I had will Cali's post is that it seemed to me he was bypassed what makes a 'good' action actually 'good'.

It didn't. See above.

Quaker wrote:I would ask you the same follow-up question I asked Cali - what makes concern for others ethically better than another evolutionary development such as behaviour where males will seek to cause harm to other males in order to propagate their genes?

Actually, you'll find even in manifestly territorial species, that combat of this sort is ritualised. I've observed this over many years amongst Cichlids in my capacity as a tropical fishkeeper, these fishes being surprisingly close to humans behaviourally. You'll find a nice, if woefully anthropomorphised, account thereof, in Dr William T. Innes' book Exotic Aquarium Fishes, which I reproduced in a past post here.

Basically, male-male competition is ritualised right across the Animal Kingdom (along with several other classes of behaviour). Indeed, I'm aware of documented instances from the scientific literature that occur in insects. Amongst the most extensively studied being the Stalk Eyed Flies (Family Diopsidae), apposite papers thereto being these:

[1] Exaggerated Male Eye Span Influences Contest Outcome In Stalk-Eyed Flies (Diopsidae) by Tami N. Panhuis & Gerald S. Wilkinson, Behavioural Ecology & Sociobiology, 46: 221-227 (Accepted 12th March 1999) [Full paper downloadable from here]

Panhuis & Wilkinson, 1999 wrote:Abstract. Evolution of male weapons or status signals has been hypothesized to precede evolution of female mating preferences for those traits. We used staged male fights among three species of Malaysian stalk-eyed flies (Diptera: Diopsidae) to determine if elongated eye span, which is preferred by females in two sexually dimorphic species, influences contest outcome. Extreme sexual dimorphism, with large males possessing longer eye span than females, is shared by Cyrtodiopsis whitei and C. dalmanni. In contrast, C. quinqueguttata exhibits a more ancestral condition - short, sexually monomorphic eye stalks. Videotape analysis of 20-min paired contests revealed that males with larger eye span and body size won more fights in the dimorphic, but not monomorphic, species. To determine if males from the dimorphic species use eye span directly to resolve contests, we competed male C. dalmanni from lines that had undergone artificial selection for 30 generations to increase or decrease eye span. We found that eye span, independently of body size, determines contest outcome in selected-line males. Furthermore, in both dimorphic species, the average encounter duration declined as the eye span dierence between contestants increased, as expected if males use eye span to assess opponent size. The number of encounters also increased with age in dimorphic, but not monomorphic, species. Selected-line males did not differ from outbred males in either fight duration or number of encounters. We conclude that exaggerated male eye stalks evolved to influence both competitive interactions and female mating preferences in these spectacular flies.

[2] Male Eye Span In Stalk-Eyed Flies Indicates Genetic Quality By Meiotic Drive Suppression by Gerald S. Wilkinson, Daven C. Presgraves & Lili Crymes, Nature, 391: 276-278 (15th January 1998) [[Full paper downloadable from here]

Wilkinson et al, 1998 wrote:In some species, females choose mates possessing ornaments that predict offspring survival1–5. However, sexual selection by female preference for male genetic quality6–8 remains controversial because conventional genetic mechanisms maintain insufficient

variation in male quality to account for costly preference and ornament evolution9,10. Here we show that females prefer ornaments that indicate genetic quality generated by transmission conflict between the sex chromosomes. By comparing sex-ratio distributions in stalk-eyed fly (Cyrtodiopsis) progeny we found that female-biased sex ratios occur in species exhibiting eye-stalk sexual dimorphism11,12 and female preferences for long eye

span13,14. Female-biased sex ratios result from meiotic drive15, the preferential transmission of a ‘selfish’X-chromosome. Artificial selection for 22 generations on male eye-stalk length in sexually dimorphic C. dalmanni produced longer eye-stalks and male-biased progeny sex ratios in replicate lines. Because male biased progeny sex ratios occurwhen a drive-resistant Y chromosome pairs with a driving X chromosome15, long eye span is genetically linked to meiotic drive suppression. Male eye span therefore signals genetic quality by influencing the reproductive value of offspring[/sup]16[/sup].

I'm aware of 14 papers in the literature on Diopsid flies, and my paper collection on these insects is far from complete.

For the record, here's a typical Stalk Eyed Fly, in this case Cyrtodiopsis dalmanni, the species featuring in the above papers:

Basically, these flies have their eyes mounted on wide stalks, hence the name, and these bizarre eye ornaments are used by the females to determine the genetic quality of potential mates. In addition, the male flies will posture before each other in a ritualised sequence, to determine which one of the antagonists gets to keep a particular territory, and hence mate with any females entering said territory. The flies don't actually attack each other, instead, they square off and gauge the size of each other's eye stalks.

Closer to my UK home, a Dolichopodid fly, Poecilobothrus nobilitatus, uses the white wingtips seen in males to perform 'semaphore' type signalling, with two different classes of signal observed - one signal for male-male competition, the other for courtship signalling to females, and I've observed these flies in action in several occasions near my home.

In the case of Cichlid fishes, many of these fishes possess the ability to change colour during the breeding season, and numerous species acquire a truly spectacular raiment of colours when setting out to reproduce. A particularly fine example is this species from Lake Victoria, namely Xystichromis phytophagus, known in the aquarium hobby as the "Christmas Fulu":

These fishes (of which the African Rift Lakes boast some 1,400 species alone), again, resort to ritualised combat in order to minimise actual injury, a feature you'll see in thousands of animal species. Far better for the species as a whole, that such competition be thus controlled, in order to minimise the risk of otherwise genetically fit individuals acquiring incapacitating injuries. Indeed, you'll find that ritualisation of combat is typically at its most developed, in those species possessing the most weapon-like tools for feeding, the deployment of said tools in anger during a territorial dispute carrying with it considerable risk of injury to both parties. Males are generally interested not in wasting vast quantities of energy kicking the shit out of each other, energy that they could better devote to actual mating, but in devising ways of seeing off competition with minimum expenditure of energy and minimum risk. But I note that all too frequently, supernaturalists have a parlous understanding of actual biology.

Now, if a mindless natural process can produce this result, namely males more interested in efficient and low risk competition, you might want to ask yourself why you, as a sentient being, were unable to work this out from first principles, when launching into your above question. Quite simply, the vast mountains of evidence available from 300 years of biological observation, let alone the actual published scientific papers, is that males generally only resort to actual warfare under significant provocation. Most of the time, the rituals are enough to establish who gets to do the shagging, and who gets to watch from the sidelines in frustration. This is before I start introducing scientific papers covering such things as homosexual insects using male-male copulation to decommission the genitalia of rivals.

Basically, from a purely practical standpoint, whatever results in us all getting along without going DEFCON 1, is generally better than behaviours that result in all the participants going nuclear at the slightest provocation. Something that's particularly pressing for our species, given that if we go DEFCON 1, we now have the capacity to destroy the entire planet 20 times over in the resulting ICBM exchanges. But once again, this brings me back to my essential point, namely, that on the basis of empathy and reciprocity, we define what is good and bad, in terms of what works within that framework. Plus, we have plenty of evidence of the shit that hits the fan when we don't do this. Namely, just about every war we've ever fought as a species, particularly in the last 100 years or so.

Quaker wrote:Cali says empathy is good - and I agree totally with him, but I didn't see any grounding for empathy being ethically superior to other developed behavours in other species.

See above.

Quaker wrote:Can Cali genuinely say some things are ethically or morally 'wrong' and base that judgement only on empiricism? I can see how the naturalist may explain how behaviours have developed, but I see nothing in there to say that one set of behaviours is ethically superior to another set of behaviours.

Once again, I cite as evidence, that ethically superior behaviours work without producing a massive body count. None of us wants to be slaughtered, after all.

Quaker wrote:I would see MacIver's acceptance of moral relativism much more in line with naturalism. Where I would have a problem with MacIver's view is that I very much doubt he (or she) can live consistently with the proposition of moral relativism where there is no real 'good' or 'bad'. Such a person would probably be regarded as a sociopath.

Strangely enough, the worst sociopaths have been those who insist upon enforcing conformity to an assertion based doctrine. See: just about every homicidal dictator in history. Another reason I have a strong antipathy for unsupported assertions.

Quaker wrote:Now, I am not making a case for God here* (though I do believe conscience is consistent with the existence of God). Rather, I am challenging the view that empiricism and naturalism allows us to determine good from bad, right from wrong, ethical behaviour from unethical behaviour, moral actions from immoral actions (pick whichever antonyms you prefer).

The points I'm making here, are that [1] at bottom, we erect axioms for the purpose of establishing ethical systems, and [2] empirical evidence certainly allows us to determine if those axioms are fulfilled by a given class of behaviours. Since reciprocity works for social species (and for a lot of others too), we choose that as our fundamental ethical axiom, and determine the ethical value of an action by empiricallly comparing the consonance of that behaviour with that axiom.

Quaker wrote:*P.S. I do not think the existence of God can be proved. I believe it is something sensed from within, and it is a lifetime's journey to make a steadily better understanding of that sense.

We've dealt with the sensus divinatus assertion before. Please don't make us break out the ordnance on that one.

Meanwhile, few of us here regard Plantinga as a real philosopher. He's a pedlar of apologetics, and a bad one at that. That you cite him in your latest post is very informative, not least with respect to your parlous understanding of biology.